In our time there is no longer a distinctly Christian way of thinking. There is to some extent a Christian ethic and even a somewhat Christian way of life and piety. But there is no distinctly Christian frame of reference, no uniquely Christian worldview, to guide our thinking in distinction from the thought of the secular world around us.

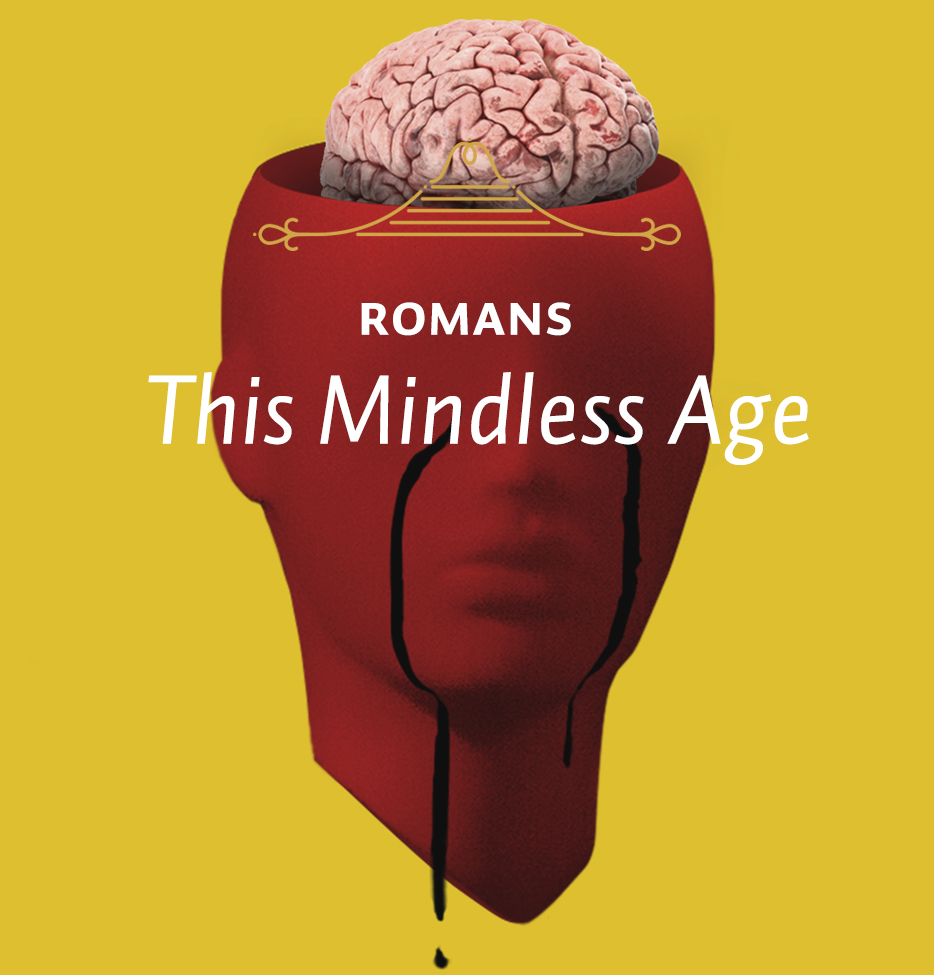

Since Christians are called to mind renewal―our text says, “Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind”—this cultural mindlessness is a major aspect of the “pattern of this world” that we are to recognize, understand, repudiate and overcome. We are to be many things as Christians, but one of them which is certainly high on the list, if not foundational to everything, is thinking people. We are to possess a “Christian mind.”

There are a number of causes for our present mindlessness—Western materialism, the fast pace of modern life and philosophical skepticism, among others—but I want to argue in this study that the chief cause is television. I began to study television as a cultural problem several years ago, and the thing that got me started was a 1987 graduation address at Duke University by Ted Koppel of ABC’s Nightline news program. Following this address Koppel was frequently quoted by Christian communicators because of something he said about the Ten Commandments. He was deploring the declining moral tone of our country and reminded his predominantly secular audience of the abiding validity of this religious standard. He said that they are Ten Commandments, not “ten suggestions,” and that they “are,” not “were” the standard. But to me the interesting thing about Koppel’s address was not what he said about the Ten Commandments, however true it was, but what he said in the very first sentence of his remarks. He said that American has become “Vannatized.”

Koppel was referring to Vanna White, the beautiful and extraordinarily popular young lady on the television game show Wheel of Fortune. Vanna White is something of a phenomenon on television. As far as her work goes, it is simple. She stands on one side of a large game board which holds blocks representing the letters of words the contestants are supposed to guess. As they guess correctly, Vanna walks across the platform turning the blocks around to reveal the letters. When she gets to the other side she claps her hands. It is simple work, but Vanna seems to like it. No, “like” is too mild a term, as Koppel notes. Vanna “thrills, rejoices, adores everything she sees.” People respond to her so well that books about her have appeared in bookstores, and she is well up on that magical but elusive list of the most admired people in America.

But here is the interesting thing. Until recently Vanna never said a word on Wheel of Fortune, and Koppel asked how a person who says nothing and who is therefore basically unknown to us can be so popular. That is just the point, he answered. Since we do not know what Vanna White is actually like, she is whatever you want her to be. “Is she a feminist or every male chauvinist’s dream? She is whatever you want her to be. Sister, lover, daughter, friend, never cross, non-threatening, and non-judgmental to a fault.”1 She is popular because we project our own deep feelings, needs or fantasies onto the television image.

Koppel does not care very much about Wheel of Fortune‘s success, of course. He was analyzing our culture. And his point is that Vanna White’s appeal is the very essence of television and that television forms our way of thinking or, to be more accurate, of not thinking. It has been hailed as the great teaching tool, but that is precisely what it does not do, because it seldom presents anything in enough depth for a person actually to think about it. Instead, it presents thirty-second flashes of events and offers images upon which we are invited to project our own vague feelings.

If all we are talking about is game shows and other forms of television entertainment, none of this would matter very much, except for the amount of time our children spend watching these banal, mind-numbing diversions rather than disciplining their minds by serious study. But if television is really conditioning us not to think, as Koppel and I maintain, then television is a serious intellectual, social, and spiritual problem.

1Ted Koppel, “Viewpoints,” Commencement Address, Duke University, May 10, 1987.